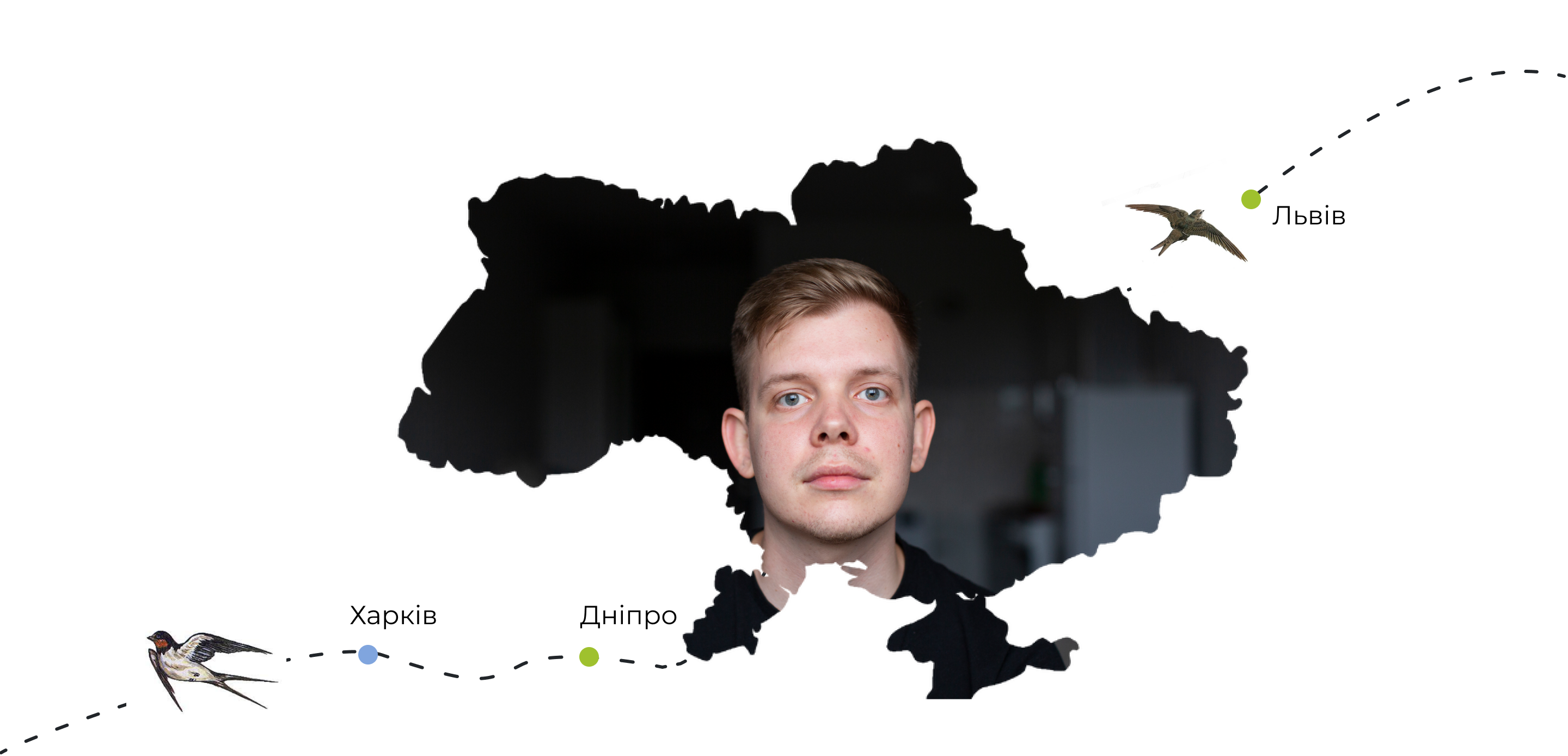

Maxym Koval,

sound Designer

Kharkiv - Dnipro - Lviv

On February 23, my girlfriend, Lena, and I came back from the movies and went to bed. At four in the morning, she woke me up and asked me to make some tea with sugar (my girlfriend is a diabetic). I went to the kitchen and made the tea. It was quiet, just a usual night. We went back to bed, and an hour later we woke up again - that time to explosions. The windows were trembling in frames, and the bed was shaking. At first, I simply thought it was thunder. But after a couple of minutes, I realised that thunder sounded different. The bursts were too long: it rattled and rumbled, and it wouldn't stop.

I called a homie and asked him if he'd heard it. He said the explosions felt stronger at his place than at mine. I asked: "What could it be?" and he said, "The worst."

Lena and I lived at my mom's at that time. I told them both to get ready to go to the subway. I hadn't yet figured out what we were going to do, but just in case, I suggested we take more stuff, so we could go somewhere far away at any moment. My mother is quite an elderly lady who had been watching the news, so she had prepared a go-bag in advance. Eventually, she didn't take it with her; I guess she just forgot.

At that time, I did not yet feel a terrible panic from the realization that the war had begun. I thought it was just provocations, that they would terrorize us with some explosions, and it all would be over. The fear kicked in later. In any situation, you have an idea of what can happen tomorrow and that you will be able to solve even some complicated stuff. But it doesn't work like that at war.

The worst feeling is that your life doesn't depend on you at all. You can't even go home, even though it feels like it is your right.

Five or seven minutes after the explosions started, I went outside to check out the situation and met a dude carrying two bottles of water. I asked him: "What's going on?" And he said, "Nothing. Explosions." He had a completely calm face. Apparently, he had it decided beforehand: "If the war starts, the first thing I'll do is go get water at 5 a.m."

First of all, we packed our belongings at my other apartment and, most importantly, took insulin. There were no train tickets, and the only option was to go by bus. We bought tickets to Dnipro and came to the bus station. We waited for three hours before we were told there would be no buses and there was no point in waiting. Still, we decided to wait, and that was when we heard the first air-raid siren. Back then, I thought that the moment the air-raid warning goes off, a plane flies over and starts bombing.

We ran to the subway and sat there till the evening. And all that time we were thinking of what to do next, where to go and how to get there. A person with diabetes needs a supply of insulin. There wasn't a huge shortage back then, but there was another problem.

The sugar test has to be done using a special blood test kit, and those were very hard to find. Without them, you couldn't tell if your sugar was low or high. On the subway, we feared that sugar could drop, there would be an urgent need to eat something sweet, and there would be no place to find it.

At 9 p.m. I got out of the subway to see what was going on out there. I asked a cab driver how much it was to get to the village of Naukovyi; there was a detached house there, where we could wait the night, and go to the West with my brother's acquaintances. The cab driver did not understand anything, he sat there shivering. Then I realised that he was shell-shocked. The only thing he said to me was, "500." I refused.

We ended up taking another cab and together with the family of our acquaintances, who had a car, we decided to go somewhere in the West. We had no idea where exactly, so we agreed to get to Dnipro first.

On the way, we saw lots of broken cars, because on the first day in this jam people crashed into fences. There were lots of car tyres in the places where there had been no military actions, just heavy panic. We drove past kilometre-long military columns, not knowing if they were our guys or the enemy's troops. Life hacks from the Internet didn't help us tell which uniforms were of swamp colour, which were olive, and which were green.

We reached Dnipro very quickly and without traffic jams. I asked to drop us off at the train station so we could take the first train. I thought of going to Lviv because there was someone to stay with. The train station was a complete fuck-up, extremely crowded, and there was physically no room in the carriages. So I decided we would better try tomorrow. I found an apartment, and we stayed there.

The next day we realized we would still have to ride on a crowded train. The hardest part was getting on. Women and children were allowed on first, and we had to hold and push back foreign students. They didn't know the language and just didn't understand that they had to give way to women and children.

In that crush my girlfriend was given a three-month-old baby so it wouldn't suffocate. Lena carried the baby somewhere into the back of the carriage. At a certain point it was no longer possible to control people, and the crowd just broke into the carriage. When I got on, I saw Lena crying; she thought I had failed to get on the train and had stayed behind.

At last, I rode on the third berth, but my mother and my girlfriend managed to get normal seats. I had very ambivalent feelings: on the one hand, I felt the pain of everyone on that train, and on the other, I felt a little joy (I don't know what to call it) that even though I was going nowhere, everyone I loved was alive, I was young, and my life hadn't been ruined. So there was a future.

Then I sent Lena and my mom to Poland. It was hard to get there from Lviv too, as the trains were packed. They were only allowed on the train because Lena had a certificate that she had a diabetes-related disability.

Before the war, I was a sound designer and recorder. I managed to evacuate some of the equipment, and now I am doing about the same in Lviv. For the first few months, I volunteered as a sound engineer, producing sound for a large number of social videos.

Some people have a bias that people in Eastern Ukraine, where we live, are somehow different from those living in Western Ukraine. I never had that. And I haven't noticed any mistreatment towards myself as a Kharkiv citizen in Lviv, either.

On the second or third day, a school friend of mine came here with his family; there were about 10 or 12 of them. They were sitting at the train station, calling all their relatives and friends, and everyone dumped them. I told a friend who hosted me in Lviv about the situation and asked him if he could take them in. I didn't really insist, because hosting so many people in a small apartment is a bit too much. But my friend agreed.

When we moved from our friends' and rented an apartment, there were no problems either. Only one landlord wanted to cheat us out of money by overcharging us for utilities. But it wasn't because we were from Kharkiv — there are people like that everywhere.

It is hard to name a specific condition under which I would return to Kharkiv. I should feel that it is safe there. When will I be able to feel it? I would really like to know.

Recorded by Misha Pravilniy

Translated by Volha Mikhnovich

Photography: Anna Bobyreva